The Influence of Epidemics on Hotel Keeping

The Influence of Epidemics on Hotel Keeping

In the throes of the COVID-19 world-wide pandemic, it became apparent how relevant our discussion of health preservation is at Hotel de Paris Museum™ and how Victorian concerns are like our own.

In addition to cooking, hosting, and debating, hotelier and restaurateur Louis Dupuy should be recognized for his interest in sanitary science. He addressed health on both an individual and communal level, what we currently call public health. Physical proof of his attention to his own health and safety, as well as his guests, is woven into the built environment of Hotel de Paris.

It could be argued Dupuy was a borderline germaphobe. His private quarters had vents and fresh air returns to rid the rooms of cigar smoke; he read books about anatomy, nutrition, health, and disease; and, he decorated in the (Charles) Eastlake style, an architectural and household design reform movement believed to improve one’s health through easy-to-clean furnishings that reduced dust, and, therefore, improved health by discouraging disease. Dupuy also embraced personal hygiene by taking daily ice baths, keeping a flesh brush and skin strap in his private bathroom, and outfitting it with hot and cold running water, a soaking tub, vanity with wash bowl and nickel plated brass spigots, a gravity flush toilet with copper cistern, and toilet paper dispensers from Scott Paper Company.

Clearly, Dupuy liked creature comforts like these; however, he also ran his famous French inn during a time of industrialization and Western expansion in the United States. People were leaving the healthful countryside for city jobs or new settlements and discovered pollution and proximity were breeding grounds for communicable diseases such as cholera, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and influenza. Because of the demand for Dupuy’s cooking and luxurious accommodations, along with an interest in outdoor sporting and restoring one’s health in the High Country, Hotel de Paris often ran at capacity. Therefore, same-sex lodgers were often asked to share rooms—and even beds—with strangers. Without social distancing, it was necessary Dupuy build sanitary features and practices into his business plan.

Corner vanities and fold-away towel bars

are located in guest rooms and private quarters, Room 4

Every room in his popular hotel contained a washstand, or, in the case of his restaurant dining room, had a lavatory adjacent to it. Dupuy encouraged (and may have even expected) his guests to engage in frequent hand washing with soap and water. The double vanity for the dining room was equipped with hot and cold running water, a cake of soap, hairbrush, comb, glass tumbler, and a towel roller and towel. Five additional roller towels were kept in a nearby walnut wardrobe, which stood outside a public half-bathroom or powder room containing a gravity flush toilet with copper cistern, corner sink, and toilet paper dispenser from Morgan Envelope Company of Springfield, Massachusetts. A nearly identical communal half-bathroom or powder room was located on the second floor, was ventilated by a skylight and reserved for the use of lodgers and possibly on-site staff.

Custom soap by James S. Kirk & Company Perfumers

Chicago, Illinois

Wash basins, toilets, and bathtubs were mostly purchased from J. L. Mott Iron Works, and regularly scoured by French housekeeper Sophie Gally who used granulated Red Seal Lye to disinfect and freshen. American chamber maid Sarah Curtain emptied and cleaned sanitary-ware chamber pots for hotel guests and on-site staff. To facilitate his lodgers’ personal hygiene, Dupuy stocked his well-ventilated guest rooms (each with one or more windows, transoms, and high ceilings for good air circulation to discourage miasmas and “bad air”) with huckaback towels and created a retail area in the restaurant dining room in which he sold five types of soap (one suited for children and others bearing the words “Hotel de Paris”), four choices of women’s perfumes, bay rum cologne for men, rose water glycerin lotion, tooth wash, and chewing gum. Doormats, toothpick holders and wastepaper baskets were also placed throughout the building.

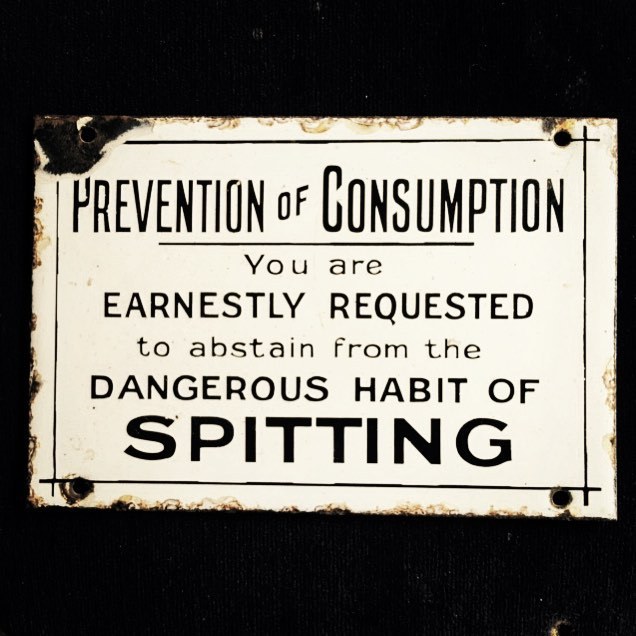

People were encouraged to use spittoons or cuspidors

Doorknobs, handles, and spittoons in the public areas of Hotel de Paris were brass. This yellow alloy of copper and zinc was known to possess anti-bacterial qualities. By 1867, French physician Victor Burq proved copper was antimicrobial and can kill bacteria and viruses within minutes; therefore, copper and brass fittings and accessories were popular not only for their attractiveness and affordability, but also for inherent health benefits.

Period example of an outdoor clothesline

Because the color white is associated with cleanliness, Dupuy’s restaurant tables were set with white tablecloths and napkins and guest beds were dressed in white sheets, pillowcases, and coverlets. Dupuy wanted to know when the linens were dingy or soiled, and employed Chinese gardener John Touk as a live-in laundryman for the hotel. Touk used a copper wash boiler for laundry and washed white linens in hot water to sterilize, lye soap to discourage bed bugs and mites, and Borax to whiten. For bleaching and sanitizing, laundry was dried out of doors on a clothesline in the sunny East Courtyard.

Copper mixing bowl on zinc countertop, 1878 Commercial Kitchen

Behind the scenes in the commercial kitchen, Dupuy prepared food on farm tables fitted with food-safe anti-bacterial zinc countertops and cooked using copper pots, pans, and mixing bowls. He prepared food wearing a heavy, white cook’s apron and cap while standing before a white porcelain cooking surface, beneath a skylight which served as a flue and between several exterior doors and windows that provided strong and consistent cross ventilation and a limitless replenishment of fresh mountain air.

Fragment of linoleum under carpet, Room 3

As healthy as Dupuy’s hotel and restaurant were, there were problems: guests shared cakes of soap, towels, a hairbrush, comb, and glass tumblers; customers touched communal fixtures; antimicrobial sheet linoleum (made popular by Frederick Watson in the 1860s) was removed and wall-to wall-carpeting installed in guest rooms; and, waitresses, musicians, and back-of-the-house staff ate soup Louis Dupuy made from restaurant leftovers salvaged from the plates of patrons.

Much like today, the Victorian era practice of sanitary science and its preservation of individual and public health was not yet perfected; however, Louis Dupuy’s interest in healthy living in the High Country resulted in good food for vitality, reduced dust indoors, free air flow, antimicrobial surfaces, sanitary plumbing fixtures, sterilized laundry, and abundant toiletries for personal hygiene.

Let’s all keep working on that social distancing!

Sign up for Our Newsletter

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy.